Into the Groove: A Brief History of Engraving

For us, the story started in 1978 – but the history of engraving itself stretches back millennia.

Britain’s very first national park, the Peak District, lies close to our central Manchester workshop. Here, in a wild and rugged landscape known today as the Dark Peak, our Neolithic and Bronze Age ancestors carved strange patterns into gritstone boulders. Some of these prehistoric carvings are roughly 6,000 years old. Naturally they’re made by hand, and primitive by modern standards.

Our business mostly deals with watches, jewellery and glassware. We’re hand engravers for the most part, but we also use computerised engraving machines when that’s appropriate.

So, how did humanity reach this point? As you’ll discover below, it’s a remarkable tale…

A Mystery from Prehistory

The Peak District is a short hop across the moors from us. Look carefully and you might just stumble across the carvings in its northern reaches.

The patterns range from simple, circular hollow ‘cups’ to zigzags, intertwining grooves, spirals and rings. Were they fertility symbols? Route markers? Hieroglyphic messages? Frankly, we can’t be sure.

Unlike the projects we work on today – the watches, glassware and jewellery that you can treasure, hold and admire – these beauties can’t be moved. All of which adds to their mystery.

But compared to our species, homo sapiens, the Dark Peak carvings aren’t actually that old. Shall we talk about the Java Shell? That’s so ancient, it’s mind-boggling.

The waters of Burbage Brook flowing among large gritstone boulders within Padley Gorge on the edge of the Dark Peak within the Peak District National Park.

Half a Million Years BC

At the end of the 19th century, this fossilised shell (along with similar freshwater mussel shells) was unearthed during a dig on Java, the Indonesian island.

More than a hundred years later, in 2007, archaeologist Stephen Munro took a much closer look at the shell collection– and found, to his astonishment, that one had been etched on.

This was no run-of-the-mill discovery. At 500,000 years old, it was the oldest example of human engraving – possibly by homo erectus, not homo sapiens – in recorded history.

A shark’s tooth, or something similar, may have been used to engrave a zigzag pattern into the palm-sized object. The shell was fresh at the time, say scientists. If that’s the case, then the cut revealed a bright white layer beneath a dark surface, like ‘dark mode’ on a computer.

Engraved ostrich eggshells found in South Africa, and bearing a simple hatched banding design, are striplings by comparison. Once used as water containers, these phenomenal artefacts date from around 60,000 BC.

Skills of the Ancient Egyptians

By the first millennium BC, engravers were using simple tools to create shallow grooves in metal jewellery. Gradually, this extended to semi-precious gemstones.

Prior to that, however, the acknowledged pioneers in stonework were the Egyptians. In the southern Nile valley, archaeologists have found more than 160 cave engravings. The largest of these – a depiction of a bull – is almost six feet wide and roughly 15,000 years old.

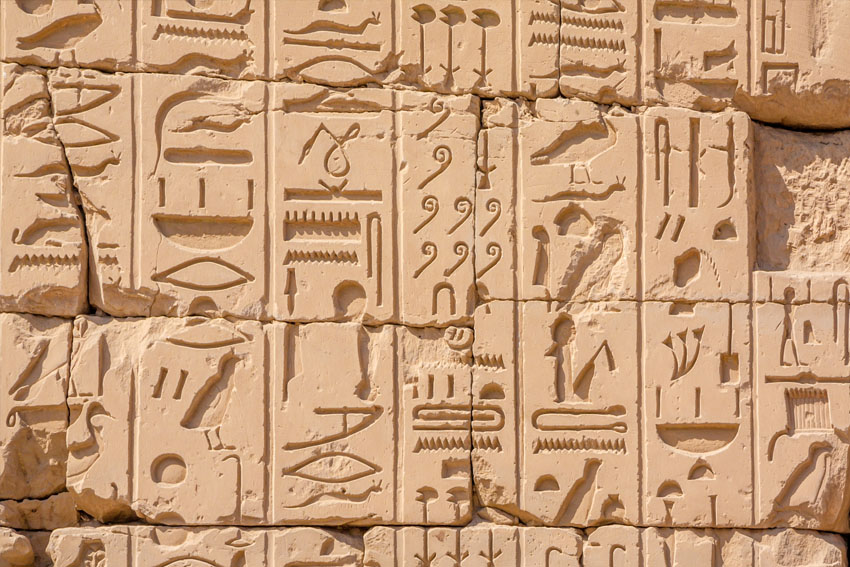

Hieroglyphics on amulets, fashioned in the shape of scarab beetles, were prized in the land of the pharaohs as a symbol of the sun god Ra.

Famously, the same kind of writing can be found in Egypt’s temples, tombs and pyramids, as well as its ancient sandstone tablets. You’ve heard of the mummy’s curse, surely?

Hieroglyphs on walls of Hypostyle Hall in Karnak Temple located in ancient Thebes, Egypt.

All Roads Lead to Rome

With the flourishing of the Roman Empire, the art and craft of engraving took further strides forward. Ornate, sometimes awe-inspiring pieces are still being discovered to this day.

Roman coins alone – cast from molten gold and silver, in engraved dies fashioned from bronze and iron – are an endless source of fascination.

By the first century AD, using an engraving wheel on glass was common practice. Often, the designs were much like those used on semi-precious stones. Decorative scenes and figures such as these offer an extraordinary window into the glory that was Rome.

Introducing the Hallmark

Jumping forward by hundreds of years, we find that medieval England was a time of widespread fraud. Engravers were highly skilled, but not always honest about their precious metals’ purity.

In a valiant effort to solve this growing problem, King Henry III tried to regulate the standard of gold and silver in 1238. Sadly, the results were mixed.

In 1300, under Edward I, a defined standard for each of these metals passed into law. So-called ‘Guardians of the Craft would engrave a leopard’s head – a King’s mark, in other words – on gold and silverware that passed their mandatory tests.

Across England, the Goldsmiths’ Company ensured that these standards were met. In the centuries that followed, more regulations came into force, such as the addition of a maker’s mark (in 1363) and a date letter (in 1478).

This completed the standard complement of hallmarks that we know today.

Evolving Innovations

Ornate decorations on swords and other arms were par for the course by the 14th century. Building on these skills, the goldsmiths of 15th century Europe were able to create increasingly detailed engravings for their jewellery, gold and silverware.

One innovation was to print impressions of their designs as a means of recording them. It’s thought that this in turn led to the printing of images on paper by way of engraved copper plates.

The burin hand tool, also known as a graver, emerged in the 16th century. Made from hardened steel, this ‘cold chisel’ can engrave a design into metal or wood.

Later, in 1603, German physicist Christoph Scheiner invented the pantograph, an engraving machine for duplicating images.

Ring engraving with gravers

Rise of the Machines

The impact of the Industrial Revolution in the 18th century changed the printing process dramatically. After the adoption of mechanical stamping, steam-powered presses became the norm.

In the Victorian era, copper fell out of favour as an engraving medium. Printing banknotes was easier with steel, for example, since the metal was so much harder.

As the 20th century dawned, the demand for engraved sporting cups, trophies and shields surged – not just for national triumphs, but for local and personal achievements.

On silver, pewter, glassware, wood or stone, inscriptions were all the rage.

Just after the Second World War, pantograph (machine engraving) enjoyed something of a revival. The tradition of hand engraving (or push engraving) fell into decline, though it proudly lives on at our Royal Exchange workshop.

Pantograph machine

Laser Focused

The emergence of lasers in the 1960s revolutionised engraving technology. As a result, designs that used to take hours can now be achieved in seconds.

The sky’s the limit as far as size and complexity are concerned. Incredibly, you can even engrave an intricate pattern in the centre of a sealed glass block.

All in all, we’ve come a long way since some enterprising hominid in Java picked up a shark’s tooth half a million years ago. So, where does John Dearden Engraving fit into this history?

Engraving in the 21st Century

The subject of engraving might seem niche – but as we’ve shown above, it’s a rich and complicated tale.

At John Dearden Engraving, what matters most isn’t our place in history as such. It’s the memories our craftwork inspires.

That’s why we say, with no little pride, that we’ve been “making it personal since 1978”.

We’re skilled in both hand and machine engraving. So, if we can bring some happy memories into your life, please get in touch.